Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! <a href="https://outsideapp.onelink.me/wOhi/6wh1kbvw" class="o-content-cta-link" data-analytics-event="click" data-analytics-data="{"name":"Element Clicked","props":{"destination_url":"https://outsideapp.onelink.me/wOhi/6wh1kbvw","domain":"<>","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}”>Download the app.

Chaturanga can be a lot like that route we regularly take to work. We move through it so frequently that it becomes a place on our way to somewhere else, an experience so routine that we hardly realize we’re doing it.

With most yoga poses, we linger for several breaths, pausing long enough to take in the teacher’s cues and adjust our alignment, alter our muscle engagement, maybe reach for the support of props. That rarely happens with Chaturanga Dandasana, which we experience only as a fleeting transition in between Plank and Urdhva Mukha Svanasana (Upward-Facing Dog).

Complicating matters is the fact that even in our strongest moments, Chaturanga is not an easy pose. So rather than hang out in it, we quickly move through it. And that can be problematic.

Why Chaturanga is So Challenging

When we rush through Chaturanga without conscious awareness, the pose becomes another expression of our usual poor postural habits. There are a lot of potential issues with that, including sagging in the lower back, but for many of us, it means our shoulders hunch and come forward, which places more weight on our anterior shoulders than they are accustomed to handling.

This misalignment happens for several reasons. Our yoga practice is the only time we support our body weight with our hands, which makes Chaturanga an innately challenging position. Complicating matters is the fact that our shoulders comprise several shallow joints, which adds to the relative difficulty in controlling these moveable parts while bearing our weight on our hands.

Also, most of us lack the upper body strength to stay committed to a low push-up position, and because many of us are already at our limit just to get there, asking us to stay longer causes us to double-down on our misaligned posture.

Even if we could remain in Chaturanga longer and give it our full attention, the fact that our shoulders are hidden from our line of sight means we lack awareness of their actual position, making it difficult to respond to specific cues.

2 Essential Cues for Chaturanga

Since the back of the body is relatively mysterious to us, we need a cue pertaining to the more familiar front body. There are two effective cues for Chaturanga that I find to be highly underrated and underutilized.

These cues are already familiar to many of us as they’re commonly offered in Plank Pose to create a stable shoulder position. But maintaining that stability becomes even more challenging when we bend our elbows and come into Chaturanga. In Plank, the downhill slope from our shoulders to feet means there’s less load running through our upper body. It takes time and practice to learn how to create stability in any weight-bearing position involving our mobile shoulder joints, but these cues can help.

1. Push the Floor Away

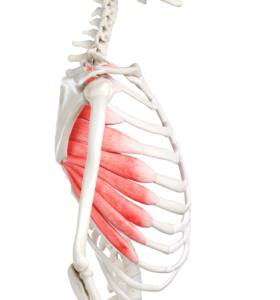

When you’re holding Chaturanga, pretend you’re using your hands to “push the floor away.” Obviously, the floor isn’t going anywhere. The pressing action instead moves your chest away from the floor by drawing your shoulder blades away from each other toward your side ribs.

Anatomy of This Cue

This is an anatomical action called protraction, which primarily engages the serratus anterior, a key stabilizing muscle that connects the inner borders of the scapula to the lateral ribs. When the serratus anterior contracts, it draws the scapula away from the spine.

Without this muscle’s support, there’s potential for the scapula to lift away from the back ribs, poking off the back in a position yoga teachers call “winging.” While not inherently injurious, winging does compromise shoulder stability. The chest, arm, and neck muscles have to make extra effort, meaning that we waste energy in every transition from Plank through Chaturanga to Upward-Facing Dog.

How to Practice This Alignment

Since shoulder control requires conscious awareness, it helps to practice scapular protraction in a less intense scenario before supporting our body weight in Chaturanga. Scapular push-ups are my go-to strengthening exercise.

Stand facing a wall with your hands firmly resting on it at shoulder height and width, as if you’re mimicking Plank Pose. Keep your head, neck, and lower back still, your arms straight, and your spine neutral. Start with scapular retraction, by moving your shoulder blades closer together and toward your spine, which will shift your sternum a little closer to the wall. Then push the wall away, gliding your shoulder blades further apart from each other and moving your sternum slightly away from the wall. Pause here in scapular protraction. Relax your neck and you might be able to feel the serratus anterior just beneath the skin of your side ribs and armpits.

Then return to scapular retraction. Repeat the pushing movement as many times as you like. When this feels natural—whether a few repetitions or a few weeks—progress the movement to Plank Pose with your knees on the mat.” progress the movement to Plank Pose with your knees on the mat. When that feels familiar, come into Plank Pose with your knees lifted. You’ll notice that your chest hollows and your shoulders roll forward.

This forward shoulder position, or rounded shoulders, is exactly what we are trying to avoid as it places unnecessary stress on the front of your shoulder joints, especially when you bend your elbows to come into Chaturanga.

Although the cue to “push the floor away” has its purpose, it unfortunately also contributes to this pattern, which is why the second underrated cue for Chaturanga is essential.

2. Broaden Your Collarbones

Once you’ve practiced pushing the floor away, it’s critical to broaden your collarbones, shine your sternum forward, or turn your chest forward. These cues reposition the head of the humerus back in the center of the shoulder socket, thereby distributing the weight of your body more evenly throughout the shoulder joint and offering you more stability and muscular support. This makes for a more efficient—and easier—transition through your vinyasa.

Anatomy of This Cue

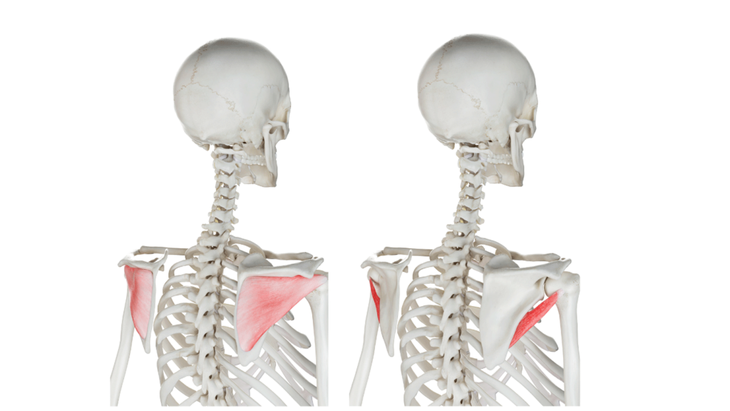

This repositioning requires you to target muscles on the back of your shoulder, including your shoulder external rotators: the infraspinatus and teres minor. This creates 360-degree support around your shoulder joints. But since the back of the body is relatively mysterious to us, we need to rely on a cue pertaining to the more familiar front body.

How to Practice This Alignment

The trick is the second cue asks you to do almost the opposite of the first cue. It takes finesse and practice to maintain both actions at once. The following movement can help you can get in touch with the subtle backward shift of the upper arm by training your body to experience shoulder external rotation.

Try this movement while lying face-down on the floor to give you a target to move away from. Take cactus arms (arms extended straight out at shoulder height, elbows bent at right angles, and palms down) and press your elbows down into the floor to lever your hands, wrists, and forearms away from the floor. It doesn’t actually matter how high your hands lift, or even whether they lift at all. You’re simply paying attention to what it feels like for your muscles to engage on the back of your shoulder blades and to feel the humeral head to stabilize. If it’s comfortable for your neck, you could even turn your head to one side at a time to watch that slight movement in your shoulders.

If your elbows don’t comfortably rest on the floor, prop them on folded blankets, towels, or yoga blocks so your elbows are grounded above the height of your hands, reducing the amount of external rotation required to start with.

Once that sensation becomes familiar, see if you can recreate it standing at a wall. Place your palms shoulder height and width against it. Push the wall away, then turn your chest forward as if a flashlight on your sternum is shining its beam up the wall toward the ceiling. The movement will be much smaller with your hands fixed in place and your arms in front of you rather than out wide, but you will feel those crucial posterior shoulder muscles switch on to hug the humeral heads back into the centers of their sockets.

When the standing version feels familiar, progress to all fours and recreate the feeling. Then come into Plank with your knees down, and then to Plank with your knees lifted.

Once you can hold both actions simultaneously with your arms strong and straight in Plank, you are ready to test out the transition to Chaturanga. Focus on maintaining the almost opposing feelings of your shoulder blades wrapping around your side ribs as your collarbones simultaneously lift and broaden, as you shift forward and bend your elbows to Chaturanga. You might feel a sense of ease and efficiency as you simply straighten your arms to transition on from Chaturanga into Upward-Facing Dog.

3 Things You Can Do to Better Understand These Cues

It’s never quick or easy to challenge our habitual patterns, so expect imperfection, especially when you start. Even though you may feel that you’re familiar with these two cues in Plank, it can help to try the following as you apply them to Chaturanga:

Lower Your Knees

Try bringing your knees to the mat as you transition from Plank into Chaturanga the first couple of times in each practice, or for as long as it takes to feel fully familiar with this new shoulder position. Reducing the load on your shoulders gives you a little more leeway to build new neuromuscular pathways without taxing the joints to their fullest extent.

Don’t Come to a 90-Degree Bend in Your Elbows

As you lower into Chaturanga, keep your shoulders higher than your elbows. When you lower your chest closer to the floor and take your elbows past a 90-degree angle, you increase the gravitational load on the fronts of your shoulders, making it increasingly difficult to maintain the central alignment of your humeral heads. Glance at your shoulders as you lower to gather visual feedback on your shoulder position rather than relying on your internal sensation regarding what previously underutilized muscles are doing.

Exploring a new, more balanced shoulder alignment in Chaturanga is significantly easier when you stay a little higher and more buoyant. This also reduces the load you are asking your shoulders to manage.

Take Your Time

You may never stay in Chaturanga long enough to explore its nuances as much as you do in other foundational poses. And you don’t have to. Perfection is not the aim of yoga practice; instead we use it as an opportunity to inhabit our bodies and our minds with more awareness. That awareness can be harnessed to disrupt our programmed patterns and pathways and experiment with new ones. If we can do that in a pose as challenging as Chaturanga, perhaps we become more able to do it in the complexities of daily life.

About Our Contributor

Rachel Land is a Yoga Medicine instructor offering group and one-on-one yoga sessions in Queenstown New Zealand, as well as on-demand at practice.yogamedicine.com. Passionate about the real-world application of her studies in anatomy and alignment, Rachel uses yoga to help her students create strength, stability, and clarity of mind. Rachel also co-hosts the new Yoga Medicine Podcast.